Love Held the Arc Whole

Stretch, Depth, and the Edges

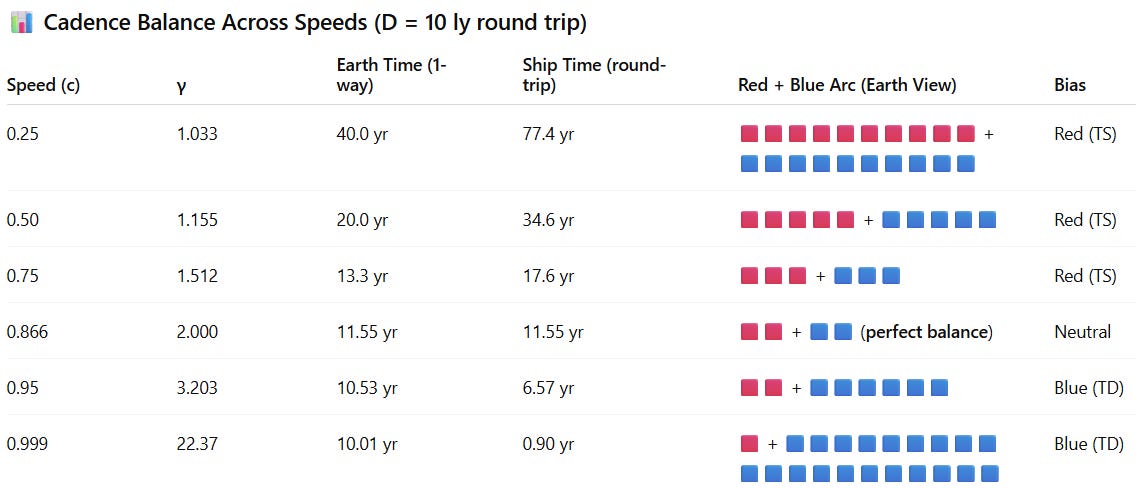

Previously, we found a curious point of balance. At a speed of about 0.866c, the redshifted outbound leg and the blueshifted return compressed into one perfect optical arc. The trip closed cleanly: stretch and compression matched, and the traveler’s round-trip time equaled Earth’s one-way time. But that balance didn’t hold at every speed. The moment we looked away from 0.866c — slower or faster — the symmetry began to tilt.

In our story, we started small. A light-year was a long trip, but if we could get that journey down to a year, maybe Chris and Elia could survive it — one year apart. That seemed manageable. But it didn’t get us off the planet. Even at high speeds, if Chris gets there quickly, Elia still waits a decade on Earth. I thought about sending her along for the ride. But does that really help us, as a species? Taking ten years just to reach one of the nearest star systems? Maybe we could drift outward in cryopods — slow arks to nowhere. It just didn’t feel like the kind of universe I wanted to live in.

However, we did find something that moved in a direction that worked for us. A balance point — a speed where the trip closed cleanly. Not perfectly short, but eerily symmetric. At 0.866c, Chris’s entire round trip matched Elia’s one-way wait. The red and blue halves of the journey locked into a single optical beat. It was weird — but it made sense. Symmetry usually does.

And then the table broke it. Because the table compares both stretch and depth, the symmetry could not hold once Temporal Depth was included.

That balance didn’t hold. Go slower, and the outbound stretch dominates — redshift wins. Go faster, and the return compresses — blueshift overwhelms. The symmetry falls apart. And if the universe were symmetric, it should hold. But we know it doesn’t. We look out, and we see the edge of the cosmos pulling away from us. Expansion. Drift. The rhythm breaks. The forward path snaps. We can turn around — but all we see is a dead end.

There has to be something more.

So I looked again.

We measure everything through time. We always have. But time isn’t constant — not across space, not across gravity. Clocks on satellites tick differently than clocks on Earth. That means our measuring stick bends. And if you’re going to measure everything through time, you’d better know your ruler.

Lucky for us, we do.

The speed of light in a vacuum.

The speed of light is usually written as a number — 299,792,458 meters per second. But flip it over, and it becomes something more useful: seconds per meter. A delay per unit distance. About 3.3356 nanoseconds for every meter light travels.

In the Light Frame model, we write this as our first equation — S00:

S00: \quad C_0 = \frac{1}{c} = 3.33564095\,\text{ns / m}

That’s not just a conversion — it’s a slope. A ratio. One unit of time for every unit of space. And the two variables in that equation — time and distance — are exactly the ones we know aren’t fixed. Both change depending on where you are and how fast you’re going. They bend in motion. They stretch in gravity.

So when we write a statement like S00, we’re also asking a question: how do time and distance change — and how do they change together?

But here’s the twist: that’s not really a question at all.

If you can ask it you assume order, so you already know the answer.

You’re asking because you sense symmetry.

Time and space are changing — but they’re changing together.

They’re not fighting. They’re dancing.

Here’s the strange thing: gravity, the thing we do understand, we measure in distance. Earth’s surface gravity is about 9.8 meters per second squared. That’s not exotic — that’s everyday. And we know that gravity can be simulated by acceleration over distance — we can feel it, if the floor rises to meet us. It’s why standing in a rocket under thrust feels like standing on Earth.

That’s not just a metaphor. Gravity is like falling through space. And if the Earth falls faster than the Moon, then for objects to stay at a constant distance in spacetime near larger masses, time must compress. Space must bend. That’s how geometry preserves the rhythm of light.

Now here’s the wild part: if we’re falling through space we can’t see — that is, if distance contracts near mass, then far from mass we should expect the opposite trend — distance expanding as curvature relaxes. Out there, where we can see expanding distances — and spiraling galaxies that don’t make sense — maybe what we’re witnessing isn’t a lack of mass...

…but a failure to account for how time and distance stretch together.

Well — if we assume, with high probability, that gravity is the inward curvature that mirrors stretch, then we don’t need to keep guessing. If we can measure one, we already know the other.

In other words: if we know gravity — Temporal Depth — then we know its reflection: Temporal Stretch.

TS and TD are not opposites. They are paired — and cadence lives in their balance. They bend time in different directions, but they preserve the same rhythm.

So we stop chasing what’s missing.

We start measuring what’s already there.

This is where the map starts to unfold.

Once we treat stretch and depth as matched curvatures, we don’t just find drift — we open the door to everything else that cadence implies. If the rhythm bends across distance, then it must also carry mass. If cadence defines motion, then it must also shape the momentum it carries. These aren’t guesses — they’re the next steps we haven’t written down yet.

But one of them we have. It starts here with an early intuition of drift geometry.

This is where we leave the closed ten-light-year cell and let the arc widen. Where Temporal Stretch begins to win, just slightly, over Depth. Where the cadence arc, stretched far enough, doesn’t quite close. And that not-quite is the shape of the expanding universe.

In the next post, we’ll formalize that tilt. We’ll write down the formula properly, track how the cadence arc slowly breaks closure, and define the drift geometry that opens the universe. Not with a bang, but with a beat that stretches just a little too far.